Fall 2012–Lake Powell

27-29 September

Transition Shock

The contrasts are mind-stretching: We moved from a rich, deep-green ponderosa pine forest, dotted with golden aspen groves, at an elevation of 9000 feet, with views of a vast plateau below us, gouged out by a river whose power is spectacular to mystical. The cool green days were followed by chilly nights, with Howie’s heater in daily service. We saw, at most, maybe 6 people a day. The only water was the invisible river, 20 miles away.

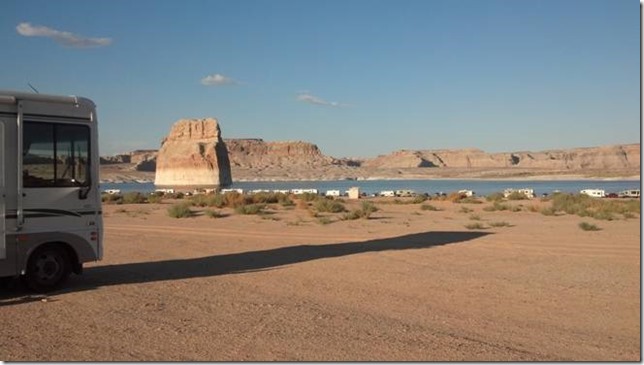

We traveled, in a few hours, one mile down through our atmosphere and 100 miles across the land, to the east. We are at Lake Powell at Page, AZ. No ponderosas, no aspens here. There is sandstone as far as the eye can see, in the most fantastic sizes, shapes, and modifications that a lifetime would not be adequate to describe. Everything is UP from here, not down. The days are in the 80’s or 90’s, and the nights drop way down into the 60’s :o) Howie’s heater is hibernating. We see about 6 people a minute. A few hundred yards from our campsite is a narrow lake that is over 200 miles long.

There are few camp sites in the area, and most are “developed”, which means closely-spaced, paved, civilized. I use the term loosely. We choose Lone Rock campground for its relative wildness – – no designated sites, just open dry-camping, our kind of style. A bit ironically, it’s also an OHV (off highway vehicle) area, which always means a bit of a crowd with noisy motorcyles (in this case quads). But it turns out, most folks want to be right at the water’s edge, which is not very important to us. So we pull back a bit, let the amusement-park crowd have its fun, and enjoy relative peace and solitude watching the masses at play.

There are few camp sites in the area, and most are “developed”, which means closely-spaced, paved, civilized. I use the term loosely. We choose Lone Rock campground for its relative wildness – – no designated sites, just open dry-camping, our kind of style. A bit ironically, it’s also an OHV (off highway vehicle) area, which always means a bit of a crowd with noisy motorcyles (in this case quads). But it turns out, most folks want to be right at the water’s edge, which is not very important to us. So we pull back a bit, let the amusement-park crowd have its fun, and enjoy relative peace and solitude watching the masses at play.

We have been so busy, re-stocking, gassing up, exploring and researching and visiting, I just have not found any time to write until now. Internet is very sporadic, with only 1X out at the Lake (no data), but some iffy-to-okay 3G in various parts of town. Here at the local Catholic church, there is 5 bars (let there be thanks).

History

On the way from the North Rim to Page, we took the time to go to Lee’s Ferry. This was a dominant feature of the area for more than 50 years, from 1871 to 1928. It is situated at the only really feasible crossing of the Colorado for something like 250 miles upstream or downstream.

I went up and down the shoreline, studying the land and trying to understand why this particular site was chosen. It just was not evident, but those folks in the late 19th century knew a LOT more than I do about how to choose transportation routes. This was the days of wagons, horses, and back-breaking labor to create roads and bridges. The ferry at Lee’s Ferry was hand-rowed back and forth across the Colorado, secured against the current by steel cables across the span. The ferry was fairly routinely swamped, overturned, or wrecked, and people were pretty routinely injured or killed. But cross the big river they did, individually and on huge freight wagons, for 50 years.

I went up and down the shoreline, studying the land and trying to understand why this particular site was chosen. It just was not evident, but those folks in the late 19th century knew a LOT more than I do about how to choose transportation routes. This was the days of wagons, horses, and back-breaking labor to create roads and bridges. The ferry at Lee’s Ferry was hand-rowed back and forth across the Colorado, secured against the current by steel cables across the span. The ferry was fairly routinely swamped, overturned, or wrecked, and people were pretty routinely injured or killed. But cross the big river they did, individually and on huge freight wagons, for 50 years.

Here’s the original site of the ferry crossing. The faint trail on the far side was and is a foot trail; there was a larger wagon trail (now faded away) higher on the bluff.

River and terrain changes have placed the visitor area about ¼ mile to the right of this picture.

Downstream from the ferry site, the river forms a “riffle” – – not smooth, but not a rapid either. The Paria River enters just between these pictures and dumps silt, debris, and turbulence into the waters of the Colorado. The ferry site is just around the corner of the right-hand bluff.

Every time I see one of these old pre-20th century historical sites, I marvel at the ingenuity, strength, perseverance, and sheer hardiness of the folks who fought their way across this tough, tough land. It amazes me every time.

On our way down H89, we passed some interesting erosion features, like these large rocks that rolled down from above and came to rest on some soft underlayment. The underlayment washed away and left them as you see them….

Page and the Dam

Something that surprised me about Page was that it literally did not exist until 1957. Page was born as a consequence of the construction of the Glen Canyon dam, which of course formed Lake Powell. Unlike the Corp of Engineers which does a lot of the construction/conservations projects in the East, the dam was built by the Bureau of Reclamation. We took a tour, and were suitably impressed by the scope of the project. The turbine blades are the size of a small garage, and there are 8 of them driving out several megawatts of power to surrounding cities.

Concrete, used to build the dam, used aggregate from an up-stream quarry. It’s the biggest, most agate-like rock I’ve EVER seen in concrete, really a surprising conglomerate. I assume the strength-tests were more than adequate; the beauty is secondary but still impressive.

Horseshoe Bend

A really charismatic curly kink in the Colorado, this place was worth the 2 mile hike in 95F sunshine (I think). It’s just south of Page, and about 1000 feet exist between the overlook and the River. Even our 28mm wide angle couldn’t get it all.

I stood up on every perch I could find, with Karin administering various admonitions and encouragements, sometimes in the same sentence. Hey, it was hot, we were confused.

As spooky as this looks, it felt even more spooky. I was using my hiking staff as an insurance policy. There is about 300 feet below me before the first bounce.

Lake Powell

Sometimes dry and vast, sometimes dark and enticing, like many lakes, Powell takes on the sky and the time of day to reveal changing character and mood.

In the evening, our camp site sits next to the sleeping giant; the sun squints goodnight through the clouds, and the bats come out to hyper-sonically nab tiny insects from mid-air in a dazzling, silent air show.

In the mornings, the clean blue sky is soaked up by the water, and beamed back to us in indigo blue.

In the mornings, the clean blue sky is soaked up by the water, and beamed back to us in indigo blue.

In the night, the full moon bathes the landscape in so much light that my poor retinal cones wake up and register faint senses of color; a hint of green in a nearby plant, a dull deep red in my polo shirt.

Tomorrow, we have relegated a few more bucks to take a lake cruise. The most expensive one offers an excursion all the way up to the Rainbow Bridge, the largest natural bridge in the world.

We learned today that an Arch is a natural (typically sandstone) formation with a pass-through underneath it. A Bridge is an Arch which spans the waterway which earlier had cut the center out of it. There are about 80 arches and bridges in this area, so we’ll see a few of them tomorrow, including the big one.

Peace

Tonight, that full moon rises over a calm lake, skipping past cloud fragments and overpowering the sky to over-shine all but the brightest stars. The lake at first tries to mimic the moon, but the flat, rippled expanse succeeds only in changing the perfect round orb into a jagged rent of silvery orange. The occasional boat slides by, its stern light slicing the gash of the distorted moon.

As the moon rises higher and higher, the lake’s efforts begin to pay off. The round moon becomes a huge, ragged oval of light across a larger and larger span of the lake. Even though the lake knows it can never perfectly reflect its heavenly partner, it tries so hard that you have to give it an E for effort. By late in the evening, the small, articulated face of the moon is magnified to a second bright sky on the surface of the lake. Despite the inaccuracies of the reflection, we forgive the lake’s errors and applaud its artistic endeavor.

We’re sitting in our camp chairs, having just finished an excellent dinner of grilled pork chops, wild rice and mixed-green salad. A touch of pinot-noir complements the meal. The distant revelry of the shoreline Disneyland is a muted murmur, non-intrusive, a mere whisper.

We marvel at the peace that we feel. We are a little more than 2 weeks into a 7-week trip. We have already forgotten some of the things we’ve seen and experienced (another good reason for these travel notes), and we are so far from needing to plan the journey back home, that we find ourselves in a rare never-never-land of seemingly infinite peace. Each day is composed of simply deciding what to do (or not do) next. If an agenda seems stressful or demanding, we just change it. Plenty of stress to be had in life without creating it yourself, right? Yes indeed.

Vehicles

One of our co-campers at Lone Rock is a French woman with a really gnarly expedition vehicle. It’s made by Scania and is apparently one of a kind. She is kind enough to invite us in, and that beast is pretty impressive. It’s a full 6-by-6, which means it has 3 axles with two wheels each, and all are fully driven. The tires are 14.5×20 and about 38” in diameter, with big beefy mud lugs about 2.5” square across the entire tread. The chassis is huge and massive, with springs that look like they are off an 18-wheeler, like 10-inch-high stacks of ½-inch thick leaf springs. Chassis rails are around 12” high and 4” wide on each side, maybe 3/8” thick steel. Diesel driven of course. Really beefy. She says she gets only 8mpg, which is what Howie gets on gas, so the overall rig is not that interesting to us for our purpose. But it’s a really interesting implementation, and everything we see and learn helps us decide what our next RV is going to be like. She got away before I could snap a pic.

30 September

More Powell

Every day, we leave Lone Rock for some activity or another, and the folks at the entry/exit gates are some of the most friendly people on the planet. One of them is Lindsey, hailing from Wisconsin. After a summer of desert temps, she’s concerned about her bones cracking next month when she returns to her homeland. Barely 5’3” and maybe 105 pounds sopping wet, she’s a cute snip of a girl with the cheeriest disposition we’ve ever seen. I think our son – – or any male under the age of 97 – – will appreciate this snapshot.

The Tour

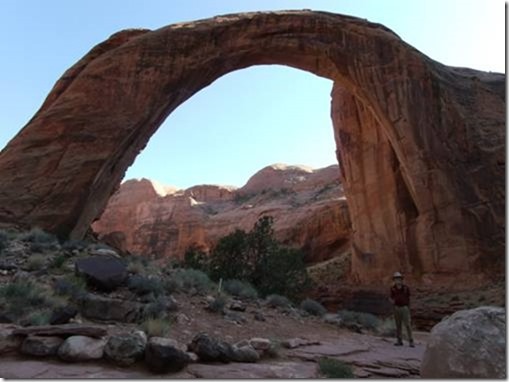

We had no plans to rent a houseboat or spend any real time on the water except with our trusty SeaRay kayak (inflatable), an activity still to come. But we did want to see a bit of the Lake besides what shows from the few roads that approach it. So we debated very little before deciding to see a chunk of the Lake (about ¼ of it) via a tourist boat tour. The clincher was that we’d be able to hike to the huge Rainbow Bridge, a massive arch over the Forbidden Canyon. The only other ways to approach this National Monument are a 17-mile, multi-day hike, or a pricey helicopter ride.

The tour boat was a pretty standard affair, with a bunch of indoor seats and a bunch of outdoor seats on the top deck. The top deck was limited to 34 people, about half of the 65 of us.

The tour boat was a pretty standard affair, with a bunch of indoor seats and a bunch of outdoor seats on the top deck. The top deck was limited to 34 people, about half of the 65 of us.

The Bridge is 42 miles away, which takes about 2 hours at the 22kts or so that the boat makes across the water. Narration was pretty good, a combination of captain’s comments and canned recordings via FM headsets.

Out on the water, an endless variety of boats present themselves. It’s hard to say how many boats are on the Lake, but with over 2,000 miles of shoreline (twice the amount of shore of the entire western US), there always seems to be plenty of room. From houseboats to ski boats to fishing boats, jet skis, work boats, tiny little runabouts and large live-aboard cabin cruisers – – they’re all there.

We left at 12:30, and the light was hard and flat and not very conducive to good photos. Later, the return trip was near sunset, and the sandstone came alive with a life of its own.

The Bridge was as impressive as all the text written about it – – a 290-foot-tall arch with a 275-foot span and a 42-foot-thick center section. After looking at eroded sandstone all day, one can’t help but wonder how long the Bridge will stand. I asked the guide if she knew how much had eroded during recorded history, but she did not. However brief or enduring this arch might be, it’s well worth the expense and the walk to see.

This first picture is a copy of a wall hanging in the Wahweap Resort, showing the arch during good-water times, when the lake level brought boats nearly to the base of the arch.

The other following pictures were taken on our hike, and the water level now is much lower, the light considerably less advantageous, and no skill is evident on my part with color balancing, saturation enhancement, etc. Ah well.

The guides were adamant about not walking under the Bridge. This is a Navajo belief and tradition; the Bridge represents the Sun’s travel over the earth, and it’s bad luck/karma (or something more Navaho-ish) to walk under it.

Even though the “Area Closed” signs were pretty clear, some of the foreign tourists didn’t understand (or didn’t choose to understand) what the restriction was. In addition, the Navajo guide must have had some bad experiences, for she was very skittish whenever a tourist got within 50 yards of being somewhere near under the Bridge. But in general everything went pretty well.

On the return trip, the sunlight was very obliging, and the low slanting rays made all the formations sit up and beg to be photographed. I complied, and I’ve tried to pick the best few of a hundred shots.

In some areas, the water mark affectionately known as the “bathtub ring” is clearly evident. This was left by the high-water peak, from mineral-laden water.

Much of the surrounding terrain rises WAY above the Lake; for reference, the water mark is about 60 feet high.

The formations behind us catch the setting sun’s rays as we head west back to Wahweap Bay and the marina.

Some of the lighting gets to be very striking indeed.

Houseboats find docks for the evening at the base of impossible structures, fishermen head back to camp for dinner past massive landmarks, and as the day fades, we find our way back to the marina, our patiently parked Howie, and eventually our own camp at Lone Rock.

Something that is probably evident from the pix, but still worthy of comment, is the fantastic size of the Glen Canyon Recreation Area (of which Lake Powell is the centerpiece). With 2000+ miles of shoreline, there is simply always an opportunity somewhere along the Lake for a dock/camp of ultimate solitude.

Every few miles on the way home from our tour, we see a solitary houseboat moored to the shore, with nobody else for miles. A pristine, almost prehistoric feeling of being alone in the wilderness.

One of the most odd idiosyncrasies of this lake is a phenomenon caused by the vertical-wall shorelines. With a typical beach-type shore, waves traveling across the water reach the beach and “break” just like ocean waves, albeit a bit smaller. However, when any wave hits a vertical, or near-vertical boundary, it simply reflects back across the water that it came from. (Yes, really, trust me on this one.)

This doesn’t have too much of an effect until you find yourself in a narrow channel with lots of boat traffic and vertical walls on both sides. This happened to me many years ago on a previous visit, and I was calmly putting along in my 26-foot ski boat, when suddenly the nose dropped about 5 feet and a wave of blue-green water swept across the top of the boat. Two kids on the bow were nearly knocked overboard, and my plexiglass windshield was knocked to pieces and washed away. About 50 gallons of water remained in the boat, which we obligingly pumped overboard with my tiny bilge pump – – for about an hour.

Normally, out on the spans of the Lake, this “rogue-wave” effect is much less, and you might simply find yourself slapped by the same boat-wake twice if you are close to shore. But I will never forget what happens when you get in tight quarters and bad timing.

1 October

G&K Kayak Tour of Lone Rock

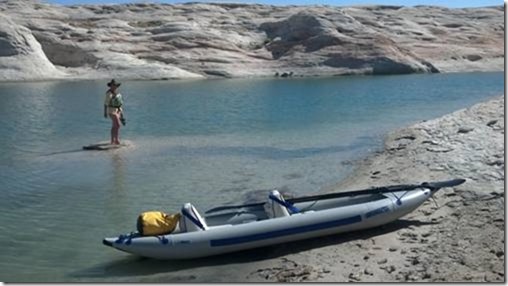

After a year and a half and no epiphanies for boat names, we have finally elected to follow our Australian friends’ lead: their continent-spanning 4×4 overland RV is named “Teefor”. This is the phoneme construction of “T for Truck”. And after long deliberation, our inflatable, sea-worthy, dual-occupant tandem Sea-Ray kayak is officially named “Beefor”. No, not Kayfor, B for Boat, get it? Good.

Beefor is a really high-quality kayak made from the same materials and structures that the river-running rafts are made of. We pump him up with a simple foot-operated bellows pump, and the finished assembly is stiff as a board and feels like you could beat on it with a hammer. Well, in fact it’s meant to be beat on by rocks, submerged branches, and the like so it’s probably that tough. In any event, it’s a confidence-builder for us neophytes, and is quite stable even in rough water.

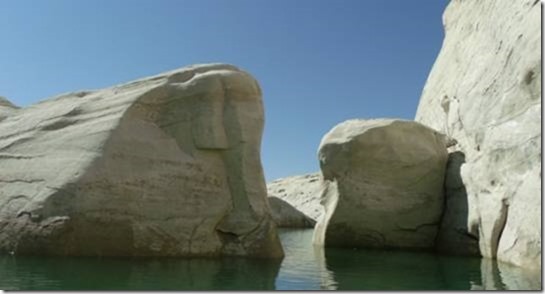

So Beefor, Karin and I went for a jaunt today. We’d heard about the narrow, skinny little vertical-wall canyons on Powell, and we saw some likely candidates on the map and decided to explore one. It’s important to note that the map is a construction of some higher-water condition of the Lake, and waterways that existed previously may be no more. No matter, we paddled away from Howie toward the monolith that marks the Lake, and then across the rest of the bay to the opposite shore.

My right shoulder, screwed-up and half-dislocated from an old injury, makes for a crunchy paddling experience, but I finally find a body angle and paddling technique that’s sustainable. Karin, my trusty tandem stoker, just faithfully synchronizes her paddles strokes with mine as we wind through the sandstone marvels. It’s kinda like on the bicycle, but, well, different too. For instance, if either of us drops the beat – unlike a tandem bike, where the pedals are chained together, our paddles are independently operated. So when one of us lapses attention, the event is announced by a loud CLACK and usually a spatter of water, as our right/left paddles intersect in mid-air. The obligatory “oops, sorry” issues from one or the other of us, and sometimes both at the same time, and then we re-focus, re-sync, and away we go again until something else distracts us. Neither one of us is in great upper-body shape, and sometimes we just get tired and stop paddling altogether. Then the other keeps on going, but velocity drops almost in half. It might sound bothersome, but it’s actually some of the greatest fun you can have with another person (especially if you crazy-love that person).

We make anywhere from 1-2mph to 4-5mph, depending on whether we are cruising and sight-seeing or just being macho, or trying to make some mileage across some choppy water.

As we pass Lone Rock, we navigate to one of the multitude of tiny tributary canyons on the far side of the bay. My phone/GPS is good at 3G on the water, and we use it to navigate. Good thing, because the blending of the sandstone makes it nearly impossible to see variations in the shoreline. At one point, we almost give up, but the map urges us on – – to an amazingly slender, winding canyon.

We follow the canyon for more than a mile, with it gradually narrowing until we can’t fit a paddle between the walls. Continuing, we eventually reach a point where the 3-foot-wide Beefor barely squeezes through, and our propulsion is by hands-on the walls of the canyon.

Throughout this passage, we are mesmerized by our adventure. This time, it’s not an adventure of surprise or excitement, but one of peace, beauty, tranquility. The water is mirror-smooth, there’s not a breath of wind. The temp is about 75F, and the sun glances off the canyon walls and water and dapples our journey. The only adequate word is idyllic. We keep looking at each other and smiling in the hugest of mutual satisfactions.

If you ever come to Powell, you should make an extra effort to buy/borrow/rent a slim little two-person craft like a canoe or kayak, and explore one or more of these tiny private byways. It is a pleasure greater than any words I can use to describe it.

If you ever come to Powell, you should make an extra effort to buy/borrow/rent a slim little two-person craft like a canoe or kayak, and explore one or more of these tiny private byways. It is a pleasure greater than any words I can use to describe it.

One of the most striking elements of our up-close experience was the amazingly soft and deteriorated condition of the sandstone which is in contact with the water. At every inch of the shoreline, the sandstone is soft, crumbling, and literally dissolving in the water (duh, what a surprise). I remember, as a kid in the ‘50s, hearing the opponents of the Glen Canyon dam project give all their objections as to why it wasn’t a good idea to immerse umpty gazillion square miles of porous rock in water. Maybe they had something…. Anyway, the sandstone is eroded by the water, and places where the waterline has existed for a while (where the Lake level stabilized) are pock-marked with caverns, scoopes, holes, cavities, and all manner of decompositions that are NOT visible in the dry reaches above the varying waterline.

Since the Lake has only been in existence for 45 years or so (not even a blink in geological time), it remains to be seen what will eventually perpetuate. It’s already well understood that the silt that used to wash down the Colorado to the sea, is now settling out in the upper reaches of Lake Powell. From my very amateur observations, I also expect that the walls and shores of the Lake will, over time, crumble to the bottom, creating a shallower and more-sloped lake. Probably won’t live to see it though.

Regardless of whatever future we may envision or fear, the present-day lake is a marvel of complexity and diversity. I can easily and without bad conscience recommend a visit to anyone with the remotest interest in such things. As much as I’ve tried to convey my impressions, the reality is so much more powerful than my words or images.

Tomorrow, we’re off into Navajo country, probably no Internet for some days…..

Comments

Fall 2012–Lake Powell — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>